About the Artist

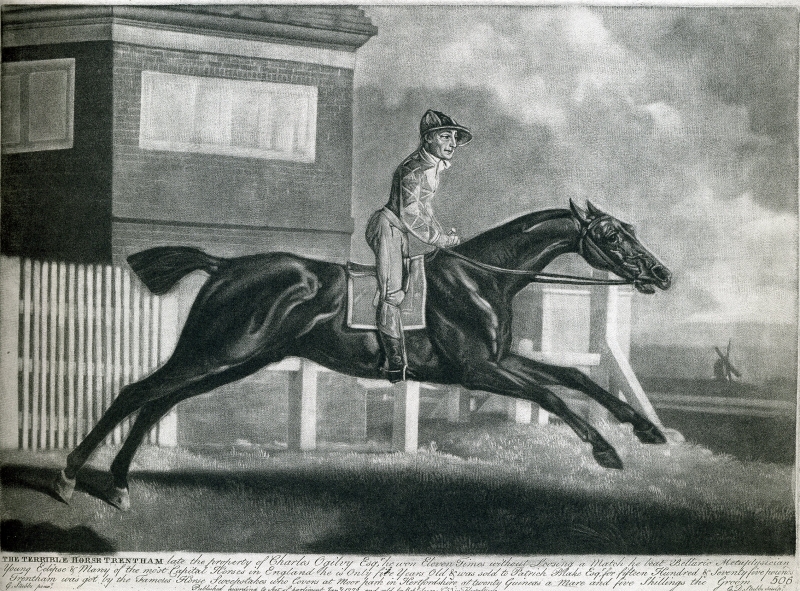

Born on 25 August 1724, the son of a Liverpool leather-dresser, George Stubbs took little interest in his father’s trade preferring to spend his time drawing. After the death of his father in 1741, Stubbs taught himself to paint and embarked upon the profession of an itinerant portrait painter in the north of England and the Midlands; he was also interested in anatomy. He went to Italy in 1754 but stayed only briefly in Rome. However, this appears to be a turning point in his career when he seemingly reached a quick maturity in his painting which included the depiction of animals. By 1756, Stubbs was living at Horkstow in Lincolnshire where by continuing to paint portraits for local patrons, he was supporting his common law wife, Mary Spencer, and his infant child, George Townly Stubbs. It was at Horkstow that he began his great work in dissecting and drawing The Anatomy of the Horse. Taking his drawings with him to London in search of an engraver in 1758 (his family may have returned to Liverpool), he surprisingly quickly established himself as a fashionable painter of the aristocracy, horses and wild animals. Between 1760 and 1765 his patrons included the Duke of Richmond, Marquess of Rockingham, Earl Grosvenor, Earl Spencer and the Duke of Grafton. He first exhibited at the Society of Artists in 1762, continuing to do so for the next thirteen years, (President in 1772). Among his most notable paintings of this period were: Whistlejacket (now in the National Gallery, London), 1761-2; The Grosvenor Hunt, 1762; the first of his series of paintings of Mares and Foals, 1762; and Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath, c.1765. His first painting of a sequence of Lion and Horse studies and that of a Zebra were exhibited in 1763. He was also engraving his drawings for The Anatomy of the Horse which was published in 1766. During the next fifteen years (1765-1780) a succession of commissioned horse portraits, portraits of dogs, paintings of wild animals, mounted and carriage conversation pieces, shooting scenes, and a series of thematically linked groups of mares and foals in pastoral landscapes of great beauty came tumbling from his brushes. In 1769 he started experimenting with painting on metal in enamels following this up with a long, but overall unsuccessful, collaboration with Wedgwood & Bentley to discover if clay could provide the ‘canvas’ for the highly coloured enamel medium. After 1775, Stubbs transferred his exhibiting allegiance to the Royal Academy, and was made an Associate in 1780. He was elected Academician the following year but refusing to present a picture as was customary, he was not given the diploma of RA. Apart from equestrian portraits, among George Stubbs’s more important paintings of the next decade were a Phaeton with Cream Ponies, 1780-5, Reapers and Haymakers, 1783 and 1785, and Labourers, 1789. The payment for commissioned work and the sale of prints of his work, etched by himself and others, provided him with a reasonable income at this period. However, despite the widespread appreciation of his talents and more than thirty productive and successful years, commissions then began to decline. Stubbs experienced financial difficulties and by 1790 his son, George Townly, was bankrupt. In the hope of alleviating this situation, Stubbs began a project to illustrate the history of horseracing through a series of engravings of important horses from the year 1750. Sixteen of these portraits of racehorses were exhibited at the Turf Gallery, engraved by his son, and published as single plates. There was little support for this venture which petered out after the publication of the fourteenth engraving: the Earl of Abingdon’s Marske, published 1 September 1796. In 1795 Stubbs also started work on his Comparative Anatomical Exposition of the Structure of the Human Body with that of a Tiger and a Common Fowl, a slightly esoteric work which was published in parts in 1804 and 1806, but never completed. During what were to become the last years of the artist’s life he worked with undiminished energy. In 1796 he portrayed Freeman, the Earl of Clarendon’s Gamekeeper with a dying Doe and a Hound, a poetic work of considerable artifice. Equally the vigour of the portrait of Hambletonian, Rubbing Down, 1800, in almost life size, yet again illustrated his already recognised manner of portraying unemotionally the strong relationship between men and animals. This large picture, 82Ω x 144Ω inches, was a remarkable painting achievement for a man now aged seventy-five. Stubbs died at 24 Somerset Street, London, where he had lived for the past forty-eight years, on 10 July 1806.